How CCR, “The Boy Scouts of Rock and Roll,” Took California and the Country by Storm

Pete Hamill’s “The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class” was published in New York magazine, the April 14 issue. The essay was a long first-person tour of the laboring white man’s plight in postindustrial America. It was simultaneously protective, defensive, judgmental, and condescending toward its subject, New York’s underemployed “working-class whites.” Hamill described them as overworked, desensitized by television, and undereducated, with no complex feelings about the world. “Most of them have only a passing acquaintance with blacks, and very few have any black friends,” for example, “so they see blacks in terms of militants with Afros and shades, or crushed people on welfare.”

Hamill shared another secret about his typical joe: “When he gets drunk, he tells you about Saipan. And he sees any form of antiwar protest as a denial of his own young manhood, and a form of spitting on the graves of the people he served with who died in his war.”

“Their grievances are real and deep,” Hamill wrote, “their remedies could blow this city apart.”

Ultimately, Hamill looked to his own class of literary people to take note of the white working class. “Our novelists write about bullfighters, migrant workers, screenwriters, psychiatrists, failing novelists, homosexuals, advertising men, gangsters, actors, politicians, drifters, hippies, spies and millionaires; I have yet to see a work of the imagination deal with the life of a wirelather, a carpenter, a subway conductor, an ironworker or a derrick operator.”

All of John’s hoodoos and haunted swamps, his lost men and oncoming revelations—it all felt traditional and comforting.As it happened, a debut novel was published to some renown in that same season, rectifying the situation slightly. Fat City was written by a thirty-five-year-old named Leonard Gardner and depicted life on the lower rungs of the central California boxing circuit. Its two heroes were Ernie, an eighteen-year-old comer, and Billy, a welterweight in his late twenties on a downhill slide. They drank and tended fitfully to their romantic relationships and traveled the long, punishing roads around Stockton, picking fruit alongside Mexican laborers between bouts.

Fat City was set in the late 1950s, but its rhythms and angry longing felt attuned to the Vietnam era. Gardner’s description of the Central Valley working class was beyond cynical, it was hellish. He described “countless lives lost hour by captive hour scratching at the miserable earth.”

The book was set largely in bars in Stockton, perhaps on the same strips where the Golliwogs played. When John, Tom, Doug, and Stu were first learning how to move an audience, they were playing to ruined men like the antiheroes in Fat City and Merle Haggard’s new hit, “Mama Tried.” Those two visions of the place were enough to make life in central California feel like a death sentence in 1969. The double-A single of “Bad Moon Rising” and “Lodi” bound that landscape to apocalypse once and for all. After the single went to no. 2, Lodi, where Leonard Gardner once lived, was now a stock image of depletion and dereliction. On the country charts, pop charts, and in book reviews, it was decreed.

Though a decade older than the Creedence men, Gardner resembled them too. He told Life magazine that his book’s title was lifted from “Negro slang” for the land of milk and honey, “a crazy goal that no one is ever going to reach.” He also shared their disillusionment with American creeds, saying that he grew up with a sense that “America was granite. When I realized that the country was coming apart it came as a shock.”

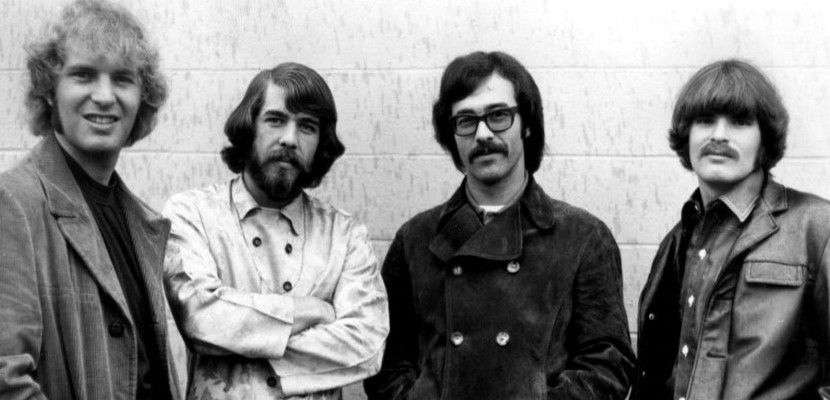

For their similar uprightness, Creedence were sometimes called “Boy Scouts” by the Fillmore crowd. It was said mostly in jest, even in envy, given their newfound fame. Paul Kantner, Airplane guitarist and Tom’s old St. Mary’s schoolmate, teased them most obnoxiously of all. But everyone noticed that Creedence stuck to beer, if that, and only after performances.

The Dead were always trying to dose them unsuspectingly. They got Doug once. He poured a cup from the wrong Fillmore coffeemaker before a set, then went down the hallway to the bathroom. The toilet began spinning, then he ran to the sink and saw the muscles of his face in the mirror. He played the set white-knuckled, biting the insides of his cheeks to stay balanced.

“The Boy Scouts of Rock and Roll,” then, because now all four were married—Stu to his girlfriend Jacalyn in 1969—not explorers of consciousness or communards in kaftans. Most people meant it well, but the El Cerrito boys were predisposed to take these comments too seriously. They played the ballrooms in San Francisco and they knew people respected them, but there was never going to be a place for them in that scene. They’d often see Janis Joplin in the halls of Fillmore West, where she was invariably teetering and clutching a bottle of Southern Comfort, accompanied by two enormous Hells Angels who steered and cleared the way for her.

By now it could be said that John had a formula: moody reminiscences about earlier times with complicated father figures, lived among the marshes.“I love y’all,” she told them once, with real joy. “You’re never playing that stupid psychedelic shit.” She promised to come see them anytime they played in town if she wasn’t touring. Her word meant something; it seemed that at least half the times they went onstage in San Francisco from that point on, they saw Janis. But what were they going to do, party with her? Any time they saw her, they were hours late to the party anyway.

The person they most related to was Bill Graham. They gave him no trouble and they met their obligations, just as the cantankerous German liked. He expected artists to show up on time, to be in shape, to deliver what the people bought their ticket for. For that attitude alone he could have been a fifth member of the band. As Creedence became more comfortable with him, they would visit in his office sharing stories and philosophies. It reinforced the band’s way of thinking to see that they shared it with the most successful promoter alive.

Graham would tear into artists for slow-walking their way through the night due to fatigue or, more likely, drugs. He complained about Hendrix in particular. In March, Creedence played a four-night residency at Fillmore West and came out for four curtain calls each night. Sixteen encores in the city’s sacred room, and the Dead still wanted to act like the cooler older brothers? Graham bought them all engraved Omega Seamaster watches and paid them cash bonuses.

They played Fillmore East that month, too, with the Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation. The New York Times sent a reporter, who took note of their “hard, firm rock in a traditional style.” After taking a swipe at psychedelic groups, the reporter praised Creedence’s “easy-rolling dynamic rock similar to a lot of early rock.” There was nothing Creedence could do to telegraph danger, it seemed. All of John’s hoodoos and haunted swamps, his lost men and oncoming revelations—it all felt traditional and comforting. A warm blanket.

When they started work on “Green River,” John’s new song, it was immediately clear he’d made another beast of a tune. This was his most aggressive yet, and “Commotion” was even deadlier. “Green River,” however, had a hard, rolling bounce, almost a snap to it. The melody was snaky and insistent. And the lyrics were more riparian coming-of-age recollections.

How could he sound like Mick Jagger, feel like a Pete Hamill schlub, and come off like Beaver Cleaver?By now it could be said that John had a formula: moody reminiscences about earlier times with complicated father figures, lived among the marshes. In “Green River” his narrator recalls another liberated time among bullfrogs and catfish. He had a rope swing and friendships with the area’s indigent, left-behind men. The kind who build the rails and the kind who ride them. The narrator knows them from “Cody’s camp,” where Old Cody Junior confides in him, “You’re gonna find the world is smolderin’ / And if you get lost, come on home to Green River.”

Through their first two albums, Creedence played songs onstage before releasing them. Since “Bad Moon Rising” and now “Green River,” they made the recordings first, which meant John thought as an arranger instead of a performer. He added acoustic guitar and a little shaker under Doug’s giant swishing hi-hats just for added swing. Slapback on the vocals. There was no unnecessary feedback or reverb in his productions. Everything was dry.

Lyrically, John wrote within the formal restrictions of the blues, and kept his descriptions as skeletal as possible. The wisps of physical detail in the new song could be read as a horror story or a bucolic romance. John insisted that Green River was just the name of a soda. But the song did grow out of his own real California childhood. His parents had taken him to Putah Creek, near Winters, between Sacramento and Napa. He might not have known a labor camp on the premises, but “Green River” was, compared to “Born on the Bayou,” a personal statement. He’d been somewhere and was thinking back on it, recalling it as a place to come back to when the world was on fire.

He could’ve used such a place himself. John made his living with a guitar, but he felt like a mug on a factory floor. He’d backed himself into sole responsibility for every aspect of the band’s success with minimal share in the rewards. How could he not be nostalgic, even for leaner times? Everything was too complicated now. And he was not prepared for this moment. There were never any records or songs about contracts and business management when he was growing up. He was at sea, even as his greatest successes came.

Around this time, Kathy Orloff, an L.A.-based music writer for the Toledo Blade, was invited to see the band’s show in Anaheim. She loved the music, but Orloff was even more struck by the men themselves. “From the records, I had the impression they were going to be Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones—very nitty gritty, tough, above the whole scene,” she wrote for her paper. The Stones were in fact preparing their first tour of America since 1966, since Brian Jones’s death. Based on their recent preoccupations, it promised to be a Dionysian assault, demonic and sexual. The Stones were committed to that bit now, they always had to up the ante.

But Creedence, to Orloff’s surprise, were nothing of the kind. “Berkeley’s Daily Californian was right when it said they are ‘a credit to the business.’ They’re both, great musicians and beautiful people. Creedence Clearwater Revival is four very nice, personable, articulate and interested young men. The kind you think you remember from high school when they played all the sock hops and sports nights. They did.”

John was mystified. How could he sound like Mick Jagger, feel like a Pete Hamill schlub, and come off like Beaver Cleaver? However it happened, he’d found the perfect combination to prevent anyone from taking him seriously. And he was the only one of the four that critics respected.

___________________________________

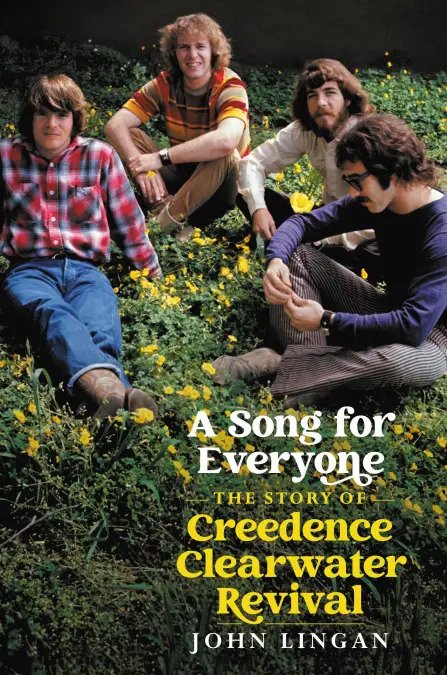

Excerpted from A Song for Everyone: The Story of Creedence Clearwater Revival by John Lingan. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.